It’s October, somehow, which means we’re settling in to one of the best times of the year. (I have to say “one of,” because when spring rolls around I’ll be like this again.) It’s the time of pumpkins and cobwebs, cauldrons and black cats, candy corns and fun-sized candy. It’s time for witches and goblins, and stories full of foggy pathways and trees that seem to lean a little too close.

I want to talk about those trees, and how they appear in fiction. I like trees. I like when they’re lush and green, when they’re transformed and changing, and when they’re bare-bones things that scritch at the side of your house. But it can feel like it’s always a creepy forest. Where’s the appreciation for the creepy stream or islet or single ominous mountain? Is there nothing eerie to be found in a silent river or an endless plain?

There is, of course, and I’m sure right now someone is ready to tell me about an example of every one of these things. In Sabriel, death is a river, endless and dangerous, likely to be full of dead things that use the river’s noise to creep up on a careless necromancer. When I think of Kerstin Hall’s The Border Keeper, I think of dangerous landscapes the likes of which I could barely imagine. In Le Guin’s “Vaster Than Empires and More Slow,” there is no getting away from the fear that takes over a group of explorers—not in the woods, and not out from under them, in a broad grassland.

What plays second fiddle to unknowable forests? Is it swamps and bogs? They turn up often, from Labyrinth’s Bog of Eternal Stench to the marshes in The Black Cauldron and The Return of the King. Damp group is tricky, unstable, treacherous; if it doesn’t suck you in, it might swallow your horse. (I will never be over Artax. Never.)

But what about caves and tunnels? They might be salvation and trap at once, as in The City of Ember, and they might just be the death of you. (I’m trying to stay away from full-on horror here, in part because I am a horror baby, but yes: The Descent did a number on my younger self’s interest in exploring caves.) They might be the place where the Balrog dwells, or where other horrors creep out from under mountains. You can’t have terrifying underground creatures without caves and tunnels. Forests can be dim and dark, but in a cave, deep underground, you can’t see anything. You are likely to be eaten by a grue.

A canyon can loom, shadows lengthening oddly. A river can snake and twist and be full of tricky rapids. An ocean is simply too big to know, though underwater eeriness is its own realm. Anywhere you can’t breathe is its own realm. Are there windy, haunted plateaus? Desperate deserts? Jemisin’s Broken Earth offers just about every geological landscape in challenging form, but I don’t remember any creepy forests. The threat comes from under the ground, not what’s growing on it.

Still, I get why it’s forests. They’re full of shadows and spiders; if you don’t know the way, every way looks the same; the trees can communicate and maybe they don’t like you. Maybe there are really big spiders. Maybe there’s whatever the insects were in that X-Files episode where people kept getting wrapped up in horrible cocoons. Maybe the thorns reach out to grab you or the trees themselves bar your way; maybe whatever lives in the woods is bigger than rabbits or even deer and bears. Maybe there’s a cottage. Maybe it’s not a cottage you want to enter.

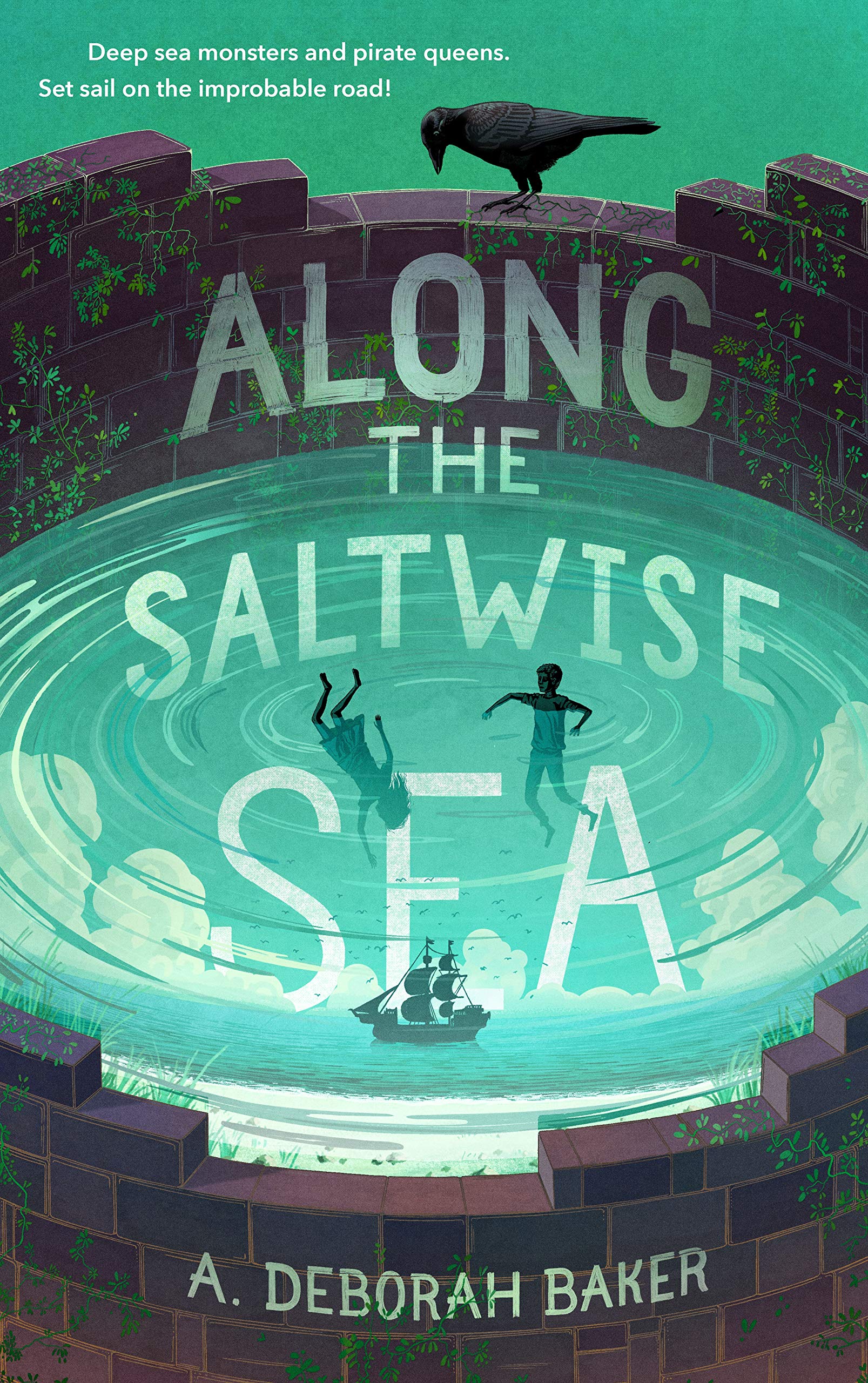

Buy the Book

Along the Saltwise Sea

When you grow up on fairy tales and Western myth, you grow up on symbolic, ever-present forests: the trees of “Hansel and Gretel,” the wall of thorns of “Sleeping Beauty,” the threat of the wolf among the trees in “Little Red Riding Hood,” the haven of the dwarves in “Snow White.” If and when you discover Tolkien, you walk through Mirkwood and Lothlorien, and meet the residents of Fangorn. The forest is beyond home, beyond safety, beyond the edge of the known world. Anything could be there. Anything is there. Can you read Norse mythology and not try to imagine Yggdrasil, the world tree? Can you be a kid who read about dryads and not begin to wonder how far they might roam? I read Lewis and wanted—maybe even more than I wanted to visit Narnia—to wander the Wood Between the Worlds.

Forests are potential, growing and ancient at once; they are shelter and threat, firewood and fallen trees, dry underbrush that might catch in a second and also a place to hide from the rain. When I was young, I tried to teach myself not to be afraid of the woods. I wanted to be an elf or a ranger. I wanted to move silently and know how to live among the trees, to befriend whatever was there. Now, when I come across a creepy forest in a book, I wonder: who hurt this place? And before long, I almost always find out.

That’s the other thing about forests: dense, rich, full of life and change and growth, they are nevertheless extremely susceptible to the whims of humans, who smother them with spells, or drive horrible things into hiding in them, or wrap them in curses and traps, or simply, carelessly, allow them to catch fire. What’s awful in a forest was almost never formed there. There’s such heaviness in this, in the way people warp the woods and fail the forests, or the ways magic—sometimes evil, sometimes just hiding—takes root under the branches.

I love the shadowy forests too, the unknowable spaces dark or growing, full of kodama or white trees that seem to have minds of their own. They’re irresistible. They could be full of magical relics or questing beasts or a witch’s cottage, a bear’s den or a treetop village. A forest, first and foremost, is a possibility.

But I think of the floating continent of Star Eater and the vast sands of Arrakis and the underground city of Frances Hardinge’s A Face Like Glass and the desolate shore of The Bone Witch—and I want to read more haunting and haunted tales that step out from under the canopy of leaves and evergreen boughs. Where else can we visit when the nights get long and the stories get a little uncanny?

Molly Templeton lives and writes in Oregon, and spends as much time as possible in the woods. Sometimes she talks about books on Twitter.